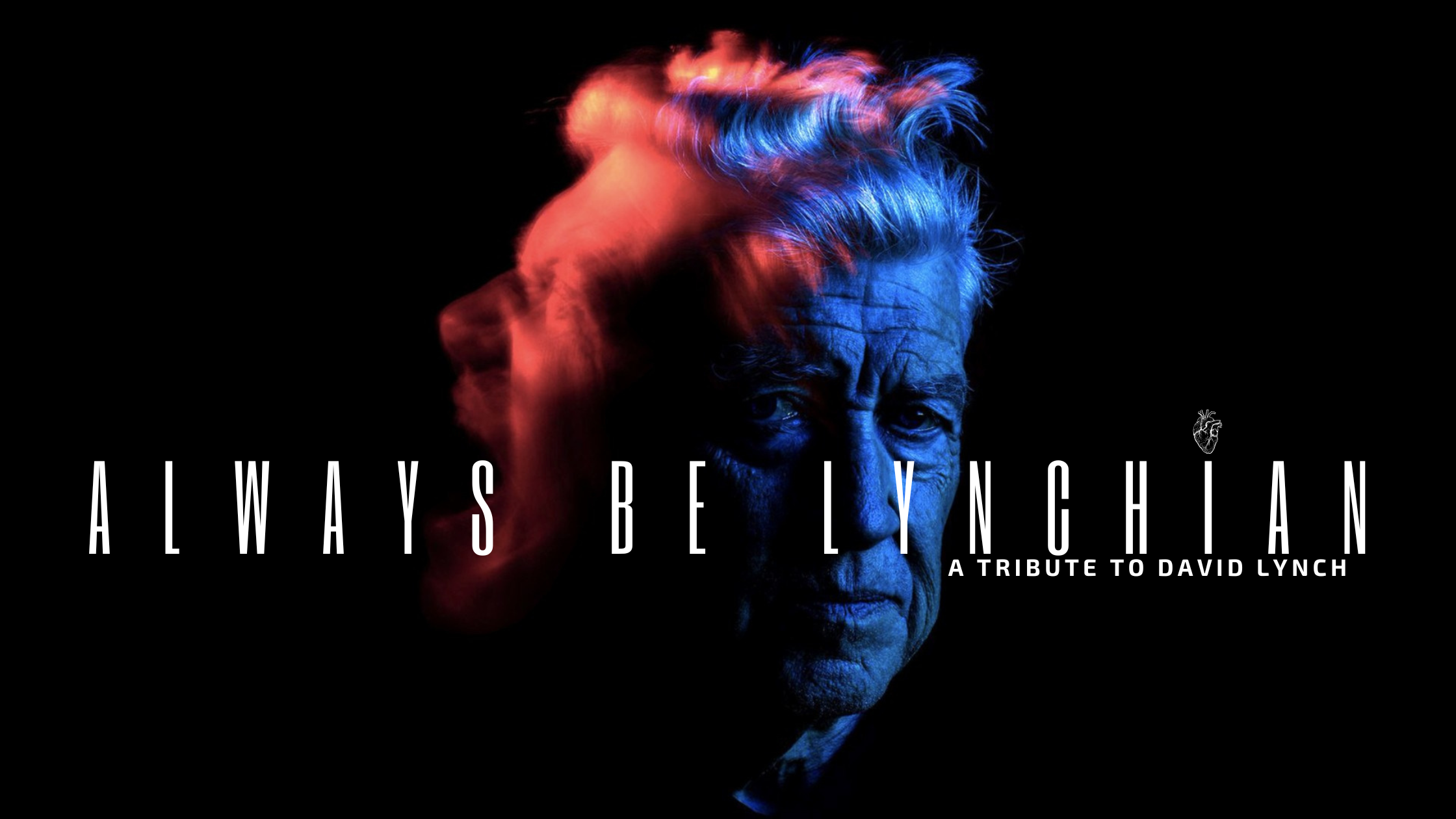

David Lynch was more than a filmmaker. He was an artist, a visionary, an author, a painter, an actor, and a musician. Lynch was skilled beyond measure and could go where other filmmakers and creators wouldn’t dare to go. He’d look behind the boundaries of imagination and lean into a surreal, experimental, and fully captivating artistic vision. We were lucky to live in the time of David Lynch. Seeing how much love, dedication, and unflinching views of his art inspires the rest of us to do what we do or want to strive to do what he did.

We at DIS/MEMBER loved him tremendously, and we would like to take the time to tell you about some of our Lynchian creations, what they mean to us, and how we could be more Lynchian in the future.

DEE HOLLOWAY

There’s been a lot of chatter in recent years around horror as a comfort object, typically tuned to the broader conversations of horror as hegemony: if X [horror is essentially sexist], then how is it that Y [horror accretes female audiences]? There’s also been a parallel, occasionally convergent discussion of “cozy” horror. Both angles home in on the transgressive fulcrum, the desire and necessity of horror to unsettle. Within any genre framework, space is made for dreaming, which at base is simply want–and dreams are sometimes nightmares.

I’m not one who finds horror comforting, per se; there are favorite films and reads I return to, but I don’t put on Texas Chainsaw as background noise while cleaning. It might be because I came to the genre late as an adult. It might be because my formative horror memories aren’t of being frightened in a group–a rite of passage, catching The Fly on TV during a sleepover, or pirating a copy of The Blair Witch to impress a crush–but of being unsettled, alone.

My horror gateway was Twin Peaks, at times, the most and least horrifying of Lynch’s creations. It helps to be exactly the wrong age to encounter an auteur organically; Lynch’s final Hollywood feature arrived in 2006, just as I embarked on my catching-up quest to watch every movie ever made. Eraserhead turned up in a film class, but it wasn’t until full adulthood, when I was exploring the alien landscapes of Cleveland, that I found myself in the car with Dale Cooper. I was so put off by the pilot episode that I closed my laptop without killing Netflix. Later that night, I woke up to Badalamenti wafting through my bedroom. My laptop had also woken, connected to wifi, and auto-played the next episode.

Obviously, now I have a Twin Peaks tattoo. The space between that initial encounter and my present self is one filled with the tension between fear and comfort, the space where the sublime and uncanny thrive. The comfort Lynch’s creations extend isn’t a security blanket but an offering of trust–that you’ll bring yourself to bear on the art and encounter the art on its terms. Comfort doesn’t arrive at the end of an episode or movie; the monster is not usually defeated, order is rarely restored, and the masks that have been removed stay off. Rather, it’s experiential, a hand lifting a red curtain to show you something you might rather have not known… but which you are now not alone in learning.

INSHA FITZPATRICK

I can barely remember the first time I “met” Laura Palmer. But I remember feeling like I’d know her for the rest of my life.

It’s an odd thing to feel about a character, but that’s what I love: characters. When characters fully come alive, I feel like the story is coming alive with it. That’s always been the thing about David Lynch’s characters that has fascinated me. For example, Dale Cooper is this wonderfully sensitive and hopeful man who falls into the mysteries of a town filled with secrets. Lulu Pace Fortune & Sailor Ripley are two outlaws taking their lives into their own hands while being madly in love. Dorothy Vallens is a fiercely complex woman who is doing what she needs to do to survive the abuse that she’s facing. Lynch’s characters are complex and detailed. They come alive in a way I’ve never seen before.

Laura Palmer, for me, is one character that has come alive more than the rest—the dead girl wrapped in plastic.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a love letter to Laura Palmer. It is horrifically beautiful, complicated, messy, and oh-so-haunting. In the show, we meet Laura, but even though she’s dead, her presence is still felt throughout Twin Peaks. They all knew Laura, loved Laura, wanted Laura, and hated Laura. With her gone, her ghosts fold over this town and uncover its mysteries bit by bit.

In Fire Walk With Me, we travel in the footsteps of Laura. It’s very rare that we walk in the footsteps of the “dead girl.” She remains an elusive mystery to us. She remains a mystery to the people who are forever changed by her. However, they memorize parts of her that they’ve projected onto her. In the film, we see Laura as a very deeply depressed and tortured teenage girl. She’s using whatever is in her power to escape from the reality of her situation. She’s lost and crying out, but she only spirals deeper down. The words come out, but no one is truly following her. They only want what Laura can offer or what they can give her.

David Lynch loved Laura Palmer. That becomes so evident in the care that he takes with her. The fact that he wanted, no, needed to tell her story. I love David Lynch’s love of cinema, art, and storytelling. However, the one thing I will remember him for is that he loved Laura Palmer. A girl who is misunderstood and had grave misfortunes. Yet she is so loved by him and by those who honor her story and keep her character alive.

JUSTIN PARTRIDGE

“I am The GREAT WENDT!”

My first interaction with Lynch was a confusing, fascinating experience. I’d like to think that he would have wanted it that way. In the 8th Grade, I came across something on Showtime during an ungodly hour of the night. I was spirited into the backroom of One-Eyed Jack’s. The most beautiful woman I had ever seen was tossed into a pressure cooker of sex work, drugs, and possibly supernatural forces – forces that howled from the din of massive redwoods and achingly bucolic surroundings. I had no idea what I was seeing or who these people were, and I had even less of an idea of what happening.

I loved every second of it and HAD to know what this was. Fire Walk With Me eluded me for years afterward – planting imagery, sounds, and performances that would never leave my mind. But that was only the start.

“Usul, we have wormsign the likes of which GOD has never seen!”

In my first year of high school, I became not-so-minorly obsessed with the works of Frank Herbert. After burning through the first run of Dune novels, The Sci-Fi Channel, excuse me, SyFy, has produced a television miniseries covering the first of the saga. I asked for the newly released DVD for Christmas. I got something else, and the next step down my own Lost Highway.

Smarter and more eloquent people have written about the saga that was David Lynch’s Dune. The film is a byproduct of the failed Jorodowsky adaption and a famously head-scratching premiere throughout festivals. But I was head over heels for it. It looked and operated like nothing I had ever seen before. I watched it constantly as I reread the books, compared it to the SyFy channel miniseries, and sought after different cuts to obtain every bit of information I could. Finally, I had my foot fully in the door, and all I could do was keep charging forward.

This was where the real hits were still awaiting me.

“In Heaven, everything is fine/ In Heaven, everything is fine/You got your good things, and I got mine.”

As I barreled into college, I finally found a Rosetta Stone in the form of a Starz Channel documentary, Midnight Movies: From The Margin to the Mainstream. Six films are featured in this doc, tracking their making, release, and subsequent impact on the “cult-classics” moniker – one of the six was Eraserhead. Lynch, a myriad of his collaborators, and film scholars were there to “explain” this movie, amongst others. But more than the hellishly fascinating scenes, the insularity of its production, the massive reaction it garnered upon its releases, and the home video transfers, I finally felt like I had a tighter grip on what it was to be “Lynchian.”

And from there, I went absolutely hog wild. From Twin Peaks, Wild at Heart, Blue Velvet (itself kicking off a lifelong obsession with the music of Roy Orbison), Eraserhead, to everything else in between. (This includes Lynch’s acting efforts and mostly hilarious cameos throughout a bunch of random shows.) I now realized what it meant to be an “auteur.” I realized how much Lynch had trickled down into all manner of things I loved. Comic books, novels, video games. Hardly any of them would be as interesting or as visually arresting without that sweetly singular, unassuming, and constantly interesting mind that kicked it all off.

His is a canon. A feeling and visual style that we are unlikely to see again. Even the best of the homages and “acolytes” have cropped up in his wake, but will likely never recreate the power and portent of The Return. They will never give the unsettlingly off-beat characters he graced us with or the powerful creative charge one experiences having just run across a Lynch effort you’ve never seen before.

A man who sprinkled stardust and who now whispers from beyond. He, himself seemed to understand better than anyone else, “Go to sleep. Everything is alright.”

[…] to approach Pacific Northwestern settings and eldritch hamlets without an inevitable comparison to Twin Peaks. The title “Evergreen” and its in-text designation as a “bad-luck place” […]