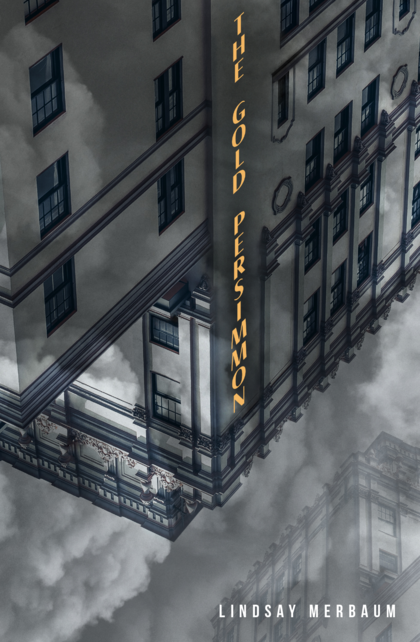

Author Lindsay Merbaum debuts on the indie horror scene with The Gold Persimmon, out now from Creature Publishing.

The Overlook. Bates Motel. The Dolphin (specifically room 1408). The Great Northern. Recently, such varied locales as the Neversink and Hotel Caiette–and now, the Gold Persimmon and Red Orchid, twin cloisters featured in The Gold Persimmon. Hotels, motels, hostels, inns: there’s something about stepping into a space that’s not your own that brings out every texture of human personality — including the darker ones. Here, Lindsay Merbaum explores those impulses and tendencies in a chat with DIS/MEMBER.

DIANA HURLBURT: As Creature Publishing bills itself a “feminist horror press,” how does The Gold Persimmon fit beneath this umbrella? Are there specific feminist-horror works–books, movies, or other media–that your book is in conversation with?

LINDSAY MERBAUM: The Gold Persimmon is a shapeshifter of a novel. It fits many genre labels, yet defies them at the same time. As a broadly-defined genre containing much crossover, I think the novel sits quite comfortably within the framework of feminist horror. Creature Publishing defines feminist horror as fiction that explores stories about gender through the tropes of horror. In many ways, Clytemnestra’s narrative is a ghost story, while Jaime faces an inexplicable fog, (an element of eco-horror, which is both a separate category and a sub-category of feminist horror), panic-induced violence, and the horrors of an enforced gender binary. Aspects of the book that readers may find jarring, such as the transition from one of these narratives to the other, contribute to the overall unsettling effect of the novel.

In an interview with The Rumpus, Ina Roy-Faderman brought up In the Dream House as another (rare) example of a story about same-sex abuse dynamics. Carmen Maria Machado has brought a lot of attention to feminist horror and contributed to revisiting certain classics, like Beloved, through a feminist horror lens. Readers might also draw a parallel between the metaphor of the house as an abusive relationship and the hotels within my novel as vessels for grief, much like the body itself.

DH: There are many doubled images in the book, from the eponymous hotel and its twin to the protagonists Cly and Jaime, to subtler imagery such as Cly’s “second skin.” Did the classic horror figure of the doppelganger inform the book’s structure or characterization?

LM: Perhaps subconsciously. I have a certain fascination with mirroring as a way of revisiting or reimagining a narrative. The Gold Persimmon also explores the nature of storytelling itself, which is reflected in its structure: the reader observes how trauma and experience become reconstituted into a new story. Certain characters are composites of one another, a kind of mirroring that reflects the influence of memory on the creative process.

DH: What are some of your horror touchstones, works that you return to or that prompted you to create horror (at any stage of your creative life)?

LM: I honestly did not realize I was writing horror until AWP in 2020. My friend Deborah Steinberg was with me and said, “You’ve got to check out this press called Creature Publishing.” Deborah is an incredible developmental editor and had worked on my book, so she knew it well. I asked her if she thought my novel could be defined as feminist horror and she was adamant that it could. That conversation changed my entire perspective on what I was writing and gave me a new framework with which to discuss it. Like many writers on the margins of mainstream literature, I wrote The Gold Persimmon for myself, because it was the kind of book I wanted to see in the world. It was only once I began taking in readers’ reactions to it that I realized which categories it might bridge, and how experimental it was.

DH: The book is subtly drenched in references to mythology, with Cly’s full name being only the tip of the iceberg. Were any specific myths in your mind as you wrote?

LM: I am slightly obsessed with mythology. (All right, more than slightly.) My spouse laughs at me for reading textbooks on Sumerian mythology and Nordic magic and mysticism, but I find it fascinating. While writing The Gold Persimmon, I thought about the minotaur quite a bit. The minotaur is a monster, set as a trap for unsuspecting sacrificial youths who are sent into his lair to be eaten. The process of writing this novel felt a lot like being lost within a labyrinth. I had a center to reach, but what would happen once I got there? The minotaur is also relevant to my interest in perspective. Some years ago, I published a story called “The Minotaur’s Mother” in Gingerbread House Magazine that retold the story of the minotaur in a modern setting from the perspective of his mother. His birth was a curse on her. But I imagined the greater torture was having her son taken from her and turned into a cannibal through abuse and neglect.

Persephone was also with me. I followed up on the story about the minotaur with an author Q&A with Gingerbread House Magazine that explores my fixation on this myth, which I previously fictionalized in a prose piece published by Anomalous Press. As a chthonic deity, Persephone fascinates me. But her lack of agency leaves a lot of holes to be filled in the story: the gods decide her fate, then renegotiate it with her mother. How she feels is not discussed. I want to explore the perspective of the Persephones of the world, the girls who are quiet because unspeakable things have happened to them. In that sense, Clytemnestra is actually my Persephone.

DH: The Gold Persimmon fits comfortably inside the haunted-house horror subgenre while expanding beyond typical film and book iterations. At the same time, the characters themselves are haunted and inhabit haunted bodies. Can you talk a bit about the body as a haunted house?

LM: There is a tremendous, terrifying force behind the imposition of binary gender because the entire premise of patriarchy and gender-based power depends upon everyone accepting and toeing the line of that binary. The effect of this plays out most dramatically in Jaime’s relationship with their body, both through dissociation and a kind of protective vigilance. Jaime must constantly observe themself from the outside to stand guard against others’ reactions to their physical presence. They live in a constant state of stress. Cly, who is a cis woman navigating the pressures to be beautiful and, at the same time, live up to her parents’ ideal, also leaves her body and observes a second self in the mirror.

If the self is forcibly split from the body, the same physical form that records trauma, then the body becomes a vessel for our pain, one we continually attempt to escape. If the body is a haunted house, then we are haunted by the very ghosts of ourselves. That is not so much frightening to me as incredibly heartbreaking.

DH: What is the most frightening aspect of your book to you?

LM: Readers often ask me how “scary” my book is, if it will give them nightmares? I always say the most frightening thing about it is the portrayal of gender discrimination so, yes, it may inspire nightmares. Just like real life.

Real ones know that spooky season doesn’t end on November 1st. If anything, the swift sunsets of Fall Back invite lingering over a haunting tome. So grab a copy of The Gold Persimmon, request a book-inspired cocktail from the author herself, and check into the hotel of your dreams (or nightmares). Thanks to Lindsay for her insights, and stay tuned for December’s “long winter nights” reading list!