Humanity’s collective obsession with the horrific in fiction has been so enduring, so persistent in its expansion into every emerging medium, that an unfathomable abyss of horror media awaits every genre aficionado. It’s more than any one person can experience — even with a canon of generally agreed-upon classics to guide us, even with the genre-junkies eagerly pointing out their favorite deep cuts. Just about every horror fan has experienced the excitement of discovering a passed-over diamond, a gem that slipped through the cracks and off of most everybody’s radar — feeling like one of the fortunate few to have stumbled on a particular tale of terror is a consistently thrilling experience for the horror fan.

Perhaps the only thing more exciting, or at least more intriguing, than stumbling upon primo slices of forgotten and unsavored horror is learning about ones that were only ever hypothetical; that were forgotten before they even had a chance to be born. Tales of terror that were only ever half-formed skeletons, abandoned mid-gestation; the might-have-beens, the could-have-beens or even should-have-beens. Even the comparatively young medium of motion picture has spawned a litany of aborted nightmares, nebulous ghosts of the unborn left behind for film scholars to ponder on. These are some of the greatest unrealized horror films, opaque designs of narrative terror that linger in the mind – even though we can only view them from the theater of our nightmares.

Clive Barker’s Godzilla

This one is a real head-turner, but the seemingly impossible pairing of influential horror author Clive Barker and Japan’s iconic monster took a tiny step toward reality in 1992. TriStar had purchased the rights to Toho’s legendary property and were in the process of soliciting story pitches for it from a variety of writers. One of these writers was none other than Barker, who eventually presented his Godzilla film concept to Sony executives in March of 1993. Producers ultimately picked Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio to script the film, but their screenplay was rejected as too expensive to produce, and eventually, the American Godzilla film ended up being Roland Emmerich’s embarrassing version.

Details of Barker’s pitch are infuriatingly scant, but the few that have emerged only make the notion that much more intriguing. Apparently, executives found Barker’s ideas “too dark” (surprise surprise), and rumor has it the story was set in New York City on the last days of 1999, perhaps indicating that his vision would have dabbled in apocalyptic themes and channeled the popularized notion that the new millennium would bring about the end of the world. Other than that, the details on Barker’s proposed King of the Monsters are nowhere to be found, but just the thought of it is fascinating.

Will It Ever Happen?: Absolutely not. It was a hell of a longshot back then, and there’s zero chance it’s happening now.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Kaleidoscope

Whatever you could say about him as a person, there is no denying the overwhelming influence of Alfred Hitchcock’s cinematic output on suspense and horror filmmaking. Kaleidoscope could have been another intriguing notch on an already impressive belt. In the mid-60s, dismayed by poor reception to his recent films and motivated by the ambitious stride of French New Wave cinema, Hitchcock developed a story outline inspired by two English serial killers, Neville Heath and John George Haigh, that made Psycho look tame. A sort of prequel to Shadow of a Doubt, Kaleidoscope (or Frenzy, as it was also titled) follows one Willie Cooper, a bodybuilder living with his overbearing mother (not unlike Psycho’s Norman Bates) who plunges into a homicidal rage when exposed to water.

The project promised to be transgressive even by the director’s standards, with explicit nudity present in the test footage photographed and gruesome violence described in Hitchcock’s screenplay (the first he had written since 1947). Even more intriguingly, Willie’s collection of bodybuilding magazines and a sequence in which his mother discovers him masturbating would have also implied him to be homosexual. Stylistically, it would have been a major departure as well, taking cues from French flourishes like handheld cameras, on location shooting with natural light, and a no-name cast.

Ultimately, the project’s adventurously shocking aim is what kept it from happening. Robert Bloch, who Hitchcock wanted to write a book of the story that he could then adapt, found the material too disturbing. Francois Truffaut expressed concerns about the emphasis on sex and nudity in correspondence with the director. The death knell came when executives at MCA/Universal — specifically Lew Wasserman, who wanted to escape the studio’s image as a maker of horror movies — thought the idea was too unsophisticated and uncommercial and had it rejected, canceling out a fascinating phase of Hitchcock’s filmography before it could even begin.

Will It Ever Happen?: Definitely not!

David Fincher’s Black Hole

Charles S. Burns’ thoroughly uncomfortable limited comic book series walks the razor-thin line between the nakedly direct and the impenetrable with commendable ease, and for that reason, no modern film director seems better suited to adapting it than David Fincher, who has shown a consistent ability to woo highbrow critics and mainstream audiences alike.

Burns’ story about a group of 1970s teenagers affected and/or infected by an STD (dubbed “the Bug”) that causes random, unpredictable mutation in its host, is illustrated in a black-and-white comic strip style that is both cartoony and uneasily realistic. It’s an aesthetic that seems perfectly primed for the director’s technical proficiency, and while Burns’ comic is difficult to classify, it features more than enough mutants, murder, and twisted behavior to have made it one of the more disturbing works in Fincher’s filmography. Unfortunately, like many of Fincher’s projects, it fell to the wayside, and the director has since become unattached.

Will It Ever Happen?: It seems so. David Fincher is no longer attached, but a year ago it was reported that Dope director Rick Famuyiwa had signed on to helm the adaptation.

Night Skies

In all likelihood, the most important unmade film on this list, Night Skies’ gestation and eventual narrative cannibalization changed the course of American cinema in the ’80s, for better or for worse. In 1978, after the success of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Columbia Pictures was predictably interested in pursuing a sequel. Steven Spielberg had no desire to pursue such a project and yet was cautious about letting Columbia develop it on their own, the way Universal had developed Jaws 2 in his absence, so he concocted a follow-up of sorts that moved away from Close Encounters’ bright and sunny vision of extraterrestrial life to something decidedly more sinister.

Largely inspired by an alleged close encounter back in 1955 in which a Kentucky family claimed they were menaced by goblin-like creatures, Spielberg came up with a treatment about a group of malevolent alien scientists who descend upon the inhabitants of a farm to conduct grisly research. Lawrence Kasdan was too busy on The Empire Strikes Back to script, so John Sayles (Piranha) was tapped to write the screenplay. Spielberg was to remain on as producer with directing duties falling to Ron Cobb (veteran production designer of Star Wars and Alien).

Production got far enough along that Rick Baker was making models and even prototypes of the creatures, but a chaotic shoot for Raiders of the Lost Ark found Spielberg longing for the soothing peace of something like Close Encounters, and when he read screenwriter Melissa Mathison the script, they both agreed that the most captivating element was the relationship between a little boy and one of the aliens. Spielberg immediately saw the value in this shift of focus, Mathison had a draft of E.T. and Me finished in eight weeks, and the rest, as they say, is history. One wonders what might have been otherwise, but even abandoned, Night Skies leaves quite a legacy.

Will It Ever Happen?: No fucking way.

George A. Romero’s Resident Evil

The Resident Evil series has left an impact on horror gaming that cannot be overstated. In relation to horror cinema, the same can certainly not be said for the Resident Evil feature films, a seemingly never-ending parade of interchangeable, cartoonish action romps. It’s a shame, because before Paul W.S. Anderson squandered the property, the father of the modern zombie himself, George A. Romero, directed a live-action commercial for Resident Evil 2 that so impressed Sony Pictures’ executives that they recruited him to write and direct an adaptation of the game.

The first draft, which Romero wrote in six weeks, was set in the Spencer Mansion, starred Chris Redfield and Jill Valentine, and featured a variety of the game’s exotic, memorable monsters. In other words, unlike Anderson’s series, it hewed very closely to the plot of the game. And for good reason — the studious Romero, who never played the game, watched a videotape of an assistant playing through it.

With so many elements to juggle, who knows how Romero’s Resident Evil would have stood up as an actual film. But we can be certain it would have been a lot better, and certainly a lot more HORROR, than the dreck movies we actually got. As it stands, the closest we’ll ever get to Romero’s version is the original ad he directed for Resident Evil 2. It might be a bit cheap and dated, but in 30 seconds, it still gets a lot closer to the games than Anderson ever did.

Will It Ever Happen?: Nope. The legendary director died in 2017. If they ever reboot the Resident Evil films into something that isn’t garbage, it won’t be by Romero’s hand.

Shadow Company

An unmade John Carpenter film is intriguing enough on its own. An unmade John Carpenter film with a screenplay by Shane Black (Predator, Lethal Weapon) and Fred Dekker (The Monster Squad, Night of the Creeps), with script contributions from to-be executive producer Walter Hill, is practically a silent scream.

Set to be Carpenter’s next project after They Live, Shadow Company told the tale of a US Special Forces team in the Vietnam War who were subject to dark, secret experiments. After they are killed and their bodies returned home, they rise from their graves to attack the town in which they were buried. The only one who stands a chance of stopping them is a haunted veteran with a mysterious link to the undead soldiers.

Carpenter favorite Kurt Russell was the planned star, and like many of Shane Black’s works, it took place on Christmas. A loud and unpretentious blueprint, Shadow Company would not have been a highbrow affair. It had the potential to channel captivating post-Vietnam themes (like Bob Clark’s similarly-minded Deathdream) and certainly would have been an exciting and unique addition to Carpenter’s already stellar filmography. There’s certainly no way it could have been worse than the truly heinous Black-Dekker (for the record that pun was completely unintentional) collaboration that recently made it to theaters, The Predator.

Will It Ever Happen?: Carpenter will never direct it, and even without him, it’s ridiculously remote. I suppose its not impossible that the screenwriters, having recently collaborated, might want to revisit this old project, but I frankly would have zero interest in seeing what current day Shane Black would do with it.

The Tourist

Clair Noto’s unproduced screenplay is a bit of a film junkie fossil, an artifact of tantalizing might-have-been that continues to fascinate. Set in 1980s Manhattan, the story follows Grace Ripley, an executive who is actually an exiled alien in disguise. She, like many other Earthbound aliens, hates the planet and views it as a backwater hell. In fact, the stress of Earth life is physically hazardous to her kind and causes them to die much more rapidly. However, no one has ever been able to get off the planet’s surface. So when a shadowy alien who runs an extraterrestrial sex club known as the Corridor enlists Grace to find “John Taiga,” a creature who may have a ship capable of escaping Earth, she journeys into the seedy underbelly of alien outcasts to find him.

This plot may be a bit more science-fiction than horror, but the screenplay’s Cronenberg-esque take on alien biology (when Grace’s kind has sex, it either rejuvenates them or kills them and their chosen mate in a desiccating cocoon) and legendary artist H.R. Giger’s nightmarish concept artwork indicate a vision that more than dabbles in the horrific, like a William S. Burroughs version of Men In Black. Whatever label one wants to give it, The Tourist promised to be a wholly original and startling vision, and it’s a shame we’ll never get to see Giger’s disturbing visions of it in live action.

Will It Ever Happen?: Almost certainly not. The screenplay has existed in limbo too long, with various elements pilfered over the years, and any version that might ever get made would likely have very little resemblance to Noto’s original vision.

At the Mountains of Madness

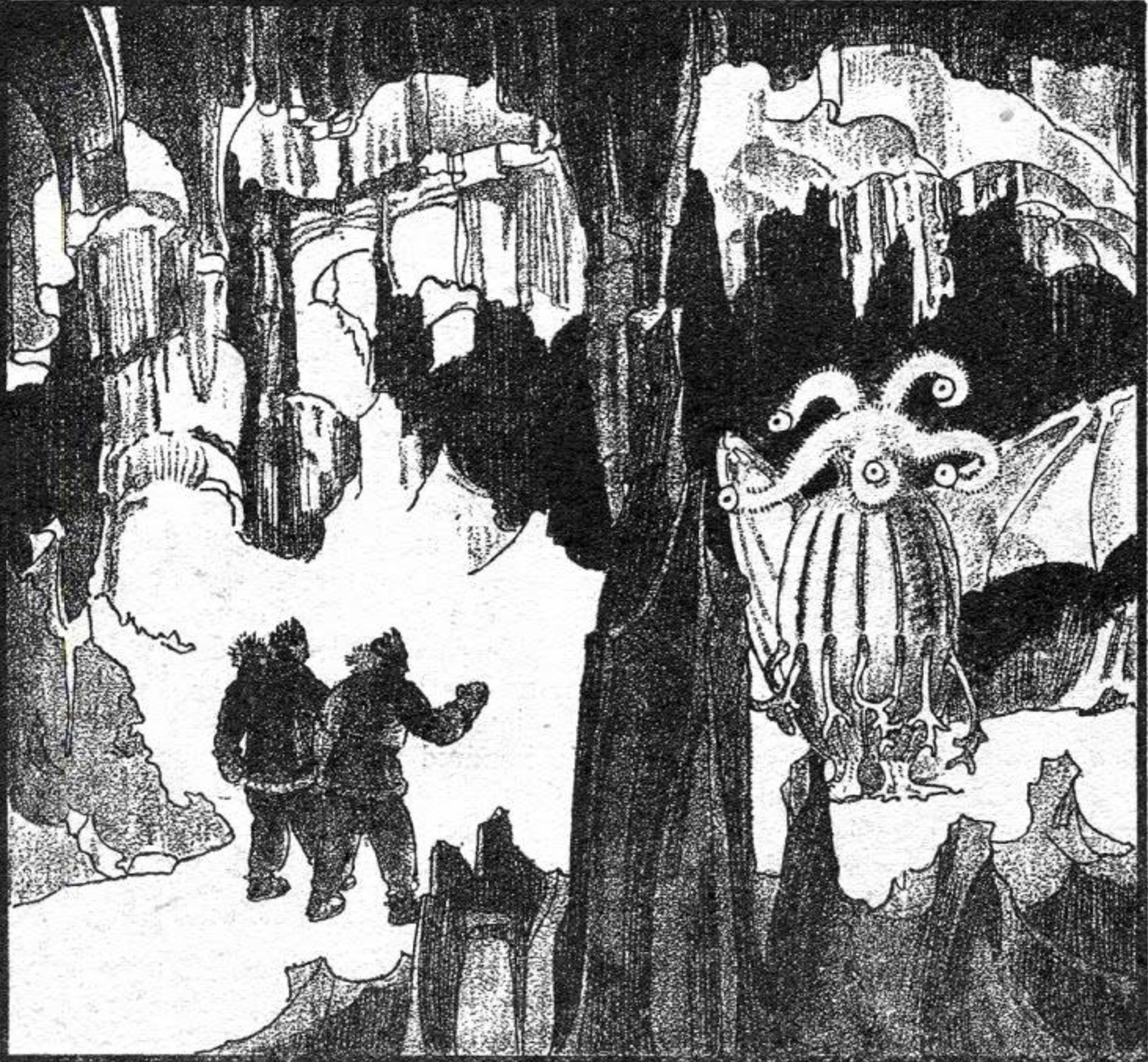

He was a loathsome racist, yes, but H.P. Lovecraft’s impact on horror has been as all-pervading yet imperceptible as the Old Gods who cast their tentacled shadows over his works. His influence is felt everywhere, and yet there has never really been an adaptation of his literature that has felt as big as his name. That might have changed if acclaimed filmmaker and genre aficionado Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth, The Devil’s Backbone) had actually been able to go through with his version of Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness.

The classic novella-length story follows a disastrous expedition to the Antarctic that results in the discovery of ancient ruins, shapeless monstrosities, and the terrible origin of humanity. Unlike any other Lovecraft adaptation, it was going to be a massive production. James Cameron was going to produce, Tom Cruise was going to star, and the budget was going to be around $150 million. A massive affair, and that was kind of the problem in the end.

Universal was sheepish about putting up so much money for an R-rated horror film, even one starring Tom Cruise and produced by James Cameron, and when del Toro stood fast against their demands for a PG-13 rating, they refused to give the project the greenlight. And so what could have been the biggest horror epic from a major studio in years tragically slipped away (del Toro later said that he believed Ridley Scott’s Prometheus would echo the “creation aspects” of At the Mountains of Madness’s narrative. Thus making the abandoned project even more redundant. This was back when all we had seen from Prometheus was the awesome trailers and none of us knew how much it was going to suck).

Will It Ever Happen?: Possible, if unlikely. del Toro still has a relatively fresh Oscar from The Shape of Water on his shelf, and there’s a chance he may one day use whatever clout he may have gained to finally realize his dream project. It’s worth a try, Guillermo — R-rating or Tom Cruise or not.