A Haunting in Venice (2023)

Directed By: Kenneth Branagh

Written By: Michael Green

Starring: Kenneth Branagh, Tina Fey, Kelly Reilly, Michelle Yeoh

Kenneth Branagh‘s third installment of the Hercule Poirot adaptations skews harder into classic horror and supernatural thrills than ever before–but do the ghostly visuals and post-war milieu deliver? Spoilers beyond!

Not being much of a Christiehead, I haven’t seen either Death on the Nile or Murder on the Orient Express, nor have I read Hallowe’en Party, the book from which A Haunting in Venice is drawn. That said, up front I’ll count A Haunting in Venice generally a success, in that it did the things I (being Old, AKA in my mid-thirties) want Hollywood movies to do.

A tempting trailer? Check! An eye-popping setting? Check! A star-studded cast? Check after check! Lighting that lets you see things? Indeed. Funky angles that remind you an actual human is behind the camera? Sure thing. Costume changes, smash cuts, poignantly creepy children, gratuitous rainfall–if there’s one thing Kenneth Branagh will do, other than blithely cast himself as the protagonist, it’s Make A Movie. As everyone knows, these days Movies are in short supply.

But is A Haunting in Venice a good movie? A good horror movie? Was it intended to be a horror movie at all? Perhaps a hot take, but Venice may fit under the umbrella of what’s being called grief horror. The Poirot books, as I understand them, are detective mysteries; the ones typically adapted are murder mysteries; but the mere presence of death (even murder) does not horror make.

Venice is concerned above all with the aftermath of grief, whether war trauma or child death or the simple fact of a life lived in fruitless pursuit of unshakable truth. Branagh’s Poirot is exhausted, retired from his work and resigned to the elusive reality of his own soul. Ariadne Oliver (Tina Fey), mystery author, goads him back to it with the temptation of unmasking Michelle Yeoh’s theatrical medium as a fraud. As the cast assembles and grows in size, each brings a measure of grief–until, drop by drop, the cup spills over.

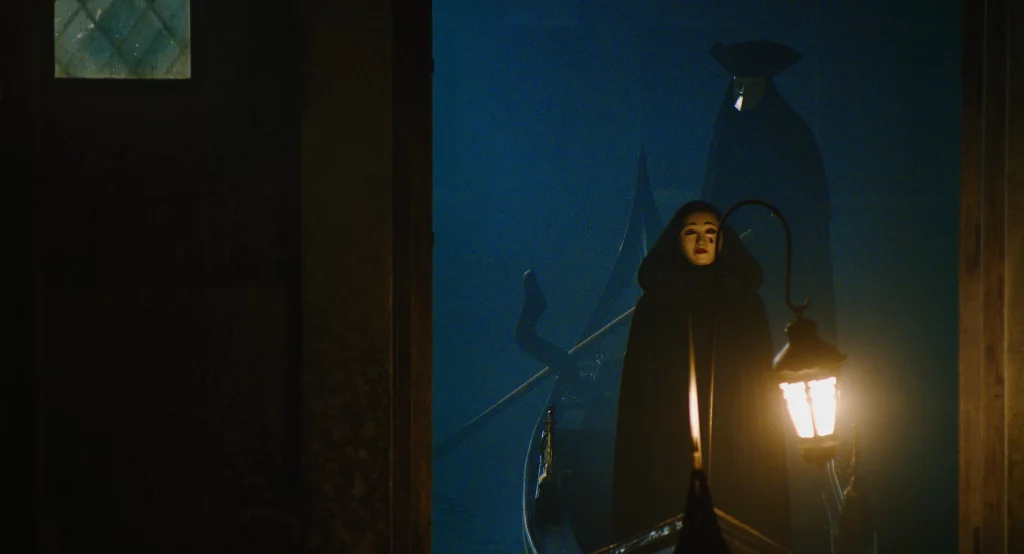

There’s much to love about the film’s setting. Venice is always a winner, beguiling and deadly in equal shares; here, black gondolas become reminiscent of hearses, Halloween masks call to Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death,” and the central palazzo’s very stones are saturated in death. The backdrop of children left to die of plague may seem too obvious in the current climate, but Venice‘s concerns are timeless.

A doctor is tormented by memories of Nazi death camps, while his son takes on the adult tasks of making sure life goes on. A pair of siblings, their childhoods stolen by genocide and war, yearn for the gilded American promise of Hollywood musicals. And a mother is so wrapped up in the idea of her child that adulthood’s onset is unbearable. Kelly Reilly, always a scene stealer, plays opera soprano Rowena Drake with coquettish venom. She alone goes through costume changes, belying her money concerns and heightening her obsession with appearance over reality.

The set-up of “debunk the spiritualist” is straightforward–and dispensed with quickly. Joyce Reynolds’ (Michelle Yeoh) unexpected death unfurls the core mystery afoot: the true nature of the death of Alicia Drake, Rowena’s daughter. It’s here that Venice becomes a vehicle worthy both of Branagh’s bombast and of considering our tempestuous times. An avaricious motif appears. Orphans eat cake at their Halloween party, Poirot bobs for apples with near-fatal consequences, and poison-sweet tea is served in fine china. Rowena is revealed to have devoured her daughter’s life, and in turn been eaten away by her own greed. Ariadne Oliver’s consumption of Poirot’s methods and character for her novels is matched only by Poirot’s own desperate hunger for satisfaction (the case solved), for relief (desire to know vanquished), for rest (ability to retire thwarted). Hunger, deprivation’s child, is the unifying factor of these characters, all of them war-struck and shellshocked.

Trance mediums like Joyce Reynolds boomed in popularity during the Civil War years in the United States. The religion’s appeal didn’t begin to wane until the 1920s, and experienced another boom during World War I. Venice’s connection of a trance medium to the World Wars is a reasonable choice–and one that resonates. Any culture rocked by mass violence or death is forced to confront its norms and mores where funeral processes, mourning, and the afterlife are concerned.

Conversely, in our own post-traumatic time, when COVID-19’s collision with the capitalist machine continues to prompt necessary artistic conversations, it feels reassuring to watch movies like Barbie, Oppenheimer, and now A Haunting in Venice. But that sensation of audience comfort comes with strings. A critical viewer may then ask themselves why we’re comforted by high-budget, star-strewn spectacles. We may explore the tension between proof of life and that life’s residence within proven properties and delivery by established names.

Venice is set a mere two years after World War II’s conclusion, and the city appears placid and beautiful, generally undamaged by violence. Yet the Drake palazzo is falling apart, composed of sets-within-sets bearing ominous impact: a garden torn to pieces, a soundproof salon, a bedroom frozen in time, a hidden cellar of bones. Examples of Venetian clockwork art punctuate the action, reminding the viewer both of the city’s glorious history and of our fraught relationship to time and reality.

If the film’s supernatural elements chiefly function as atmosphere, they’re still fun to watch, while outrageous high angles and left-of-center perspectives draw the viewer into the film’s unsettled inner world. As layers of characters and places peel away, the eternal form of the Gothic emerges, the resilience and insidious power of memory. While ultimately not spooky or gory enough to warrant Halloween release timing, A Haunting in Venice should whet the appetite of anyone hungry for old-school Hollywood pleasure. But it may also leave you excavating your own desires as a viewer, unmasking your own role in the Hollywood machine.